Offside (association football)

Offside is Law XI in the publication Laws of the Game written by the IFAB and published by FIFA. The law states that, if a player is in an offside position when the ball is touched or played by a team mate, he may not become actively involved in the play. A player is in an offside position if he is closer to the opponent's goal line than both the ball and two opposing players, but only if the player is on his opponent's half of the field (pitch). What is considered actively involved has become the subject of complex guidance.

Contents |

Application

The application of the offside rule may be considered in three steps: offside position, offside offence and offside sanction.

Offside position

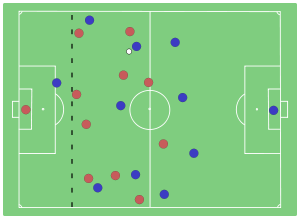

A player is in an offside position if he is in his opponents' half of the field (pitch) and is closer to his opponents' goal line than both the ball and all but zero or one of his opponents. Put another way, an offside position has three components, all of which must be satisfied for the player to be in the offside position: First, the player must be on the opposing team's half of the field. Second, the player must be in front of the ball. And third, there must be fewer than two opposing players between him and the opposing goal line, with the goalkeeper counting as an opposing player for these purposes.

The 2005 edition of the Laws of the Game included a new International Football Association Board decision that stated being "nearer to an opponent's goal line" meant that "any part of his head, body or feet is nearer to his opponents' goal line than both the ball and the second-last opponent (the last opponent typically being the goalkeeper). The arms are not included in this definition."[1] This is taken to mean that any part of the attacking player named in this decision has to be past the part of the second-last defender closest to his goal line (excluding the arms) and past the part of the ball closest to the defenders' goal line.

It is not necessary that the goalkeeper be one of the last two opponents. Any attacker that is even with or behind the ball is not in an offside position and may never be sanctioned for an offside offense. Regardless of position, there is no offside offense if a player receives the ball directly from a goal kick, corner kick, or throw-in.

IFAB has clarified in the 2009-2010 Laws of the Game that a player temporarily off the field of play is considered to be ON the boundary line at the point that he crossed over the boundary line.[2]

Offside offence

A player in an offside position at the moment the ball is touched or played by a team-mate is only committing an offside offence if, in the opinion of the referee, he becomes actively involved in play by

- Interfering with play

- Playing or touching the ball

- Interfering with an opponent

- Preventing the opponent from playing the ball by obstructing the player's sight or intentionally distracting the opponent

- Gaining an advantage by being in an offside position

- Playing the ball after the ball has rebounded off the goal, the goalkeeper, or any opponent[3]

Since offside is judged at the time the ball is touched or played by a team-mate, not when the player receives the ball, it is possible for a player to receive the ball significantly past the second-to-last defender, or even the last defender (typically the goalkeeper).

Determining whether a player is in "active play" can be complex. FIFA issued new guidelines for interpreting the offside law in 2003 and these were incorporated in Law XI in July 2005. The new wording seeks to define the three cases more precisely.

Controversy regarding offside decisions often arises from assessment of what movements a player in an offside position can make without being judged to be interfering with an opponent. Bill Shankly made a famous quote: "If a player is not interfering with play or seeking to gain an advantage, then he should be!" This quote exemplifies why IFAB had to clarify what "gaining an advantage" means, as referees all over the world were considering almost anything as an advantage.

Offside sanction

The restart for an offside sanction is an indirect free kick for the opponents where the offside-positioned player was when the ball was played or touched by a teammate. This is defined as where the infringement took place.

Officiating

In enforcing this rule, the referee depends greatly on an assistant referee, who generally keeps in line with the second-to-last defender, the ball, or the halfway line, whichever is closer to the goal line of his relevant end. An assistant referee signals that an offside offence has occurred by first raising his or her flag upright without movement and then, when acknowledged by the referee, by raising his or her flag in a manner that signifies the location of the offence:

- Flag pointed downwards: offence has occurred in the third of the pitch nearest to the assistant referee;

- Flag horizontal to the ground: offence has occurred in the middle third of the pitch;

- Flag pointed upwards: offence has occurred in the third of the pitch furthest from the assistant referee.

The assistant referees' task with regards to offside can be difficult, as they need to keep up with attacks and counter-attacks, consider which players are in an offside position when the ball is played, and then determine whether and when the offside-positioned players become involved in active play. The risk of false judgement is further increased by the foreshortening effect, which occurs when the distance between the attacking player and the assistant referee is significantly different from the distance to the defending player, and the assistant referee is not directly in line with the defender. The difficulty of offside officiating is often underestimated by spectators. Trying to judge if a player is level with an opponent at the moment the ball is kicked is not easy: if an attacker and a defender are running in opposite directions, they can be two metres apart in a tenth of a second.

Some researchers believe that offside officiating errors are "optically inevitable".[4] It has been argued that human beings and technological media are incapable of accurately detecting an offside position quickly enough to make a timely decision.[5] Sometimes it simply is not possible to keep all the relevant players in the visual field at once.[6] There have been some proposals for automated enforcement of the offside rule.[7]

History

Offside rules date back to codes of football developed at English public schools in the early nineteenth century. These offside rules were often much stricter than that in the modern game. In some of them, a player was "off his side" if he was standing in front of the ball. This was similar to the current offside law in rugby, which penalises any player between the ball and the opponent's goal. By contrast, the original Sheffield Rules had no offside rule, and players known as "kick-throughs" were positioned permanently near the opponents' goal.

In 1848, HC Malden held a meeting at his Trinity College, Cambridge rooms, that addressed the problem. Representatives from Eton, Harrow, Rugby, Winchester and Shrewsbury schools attended, each bringing their own set of rules. They sat down a little after 4pm and, by five to midnight, had drafted what is thought to be the first set of "Cambridge Rules". Malden is quoted as saying how "very satisfactorily they worked".

Unfortunately no copy of these 1848 rules exists today, but they are thought to have included laws governing throw-ins, goal-kicks, halfway line markings, re-starts, holding and pushing (which were outlawed) and offside. They even allowed for a string to be used as a cross bar.

A set of rules dated 1856 was discovered, over a hundred years later, in the library of Shrewsbury School. It is probably closely modelled on the Cambridge Rules and is thought to be the oldest set still in existence. Rule No. 9 required three defensive players to be ahead of an attacker who plays the ball. The rule states:

If the ball has passed a player and has come from the direction of his own goal, he may not touch it till the other side have kicked it, unless there are more than three of the other side before him. No player is allowed to loiter between the ball and the adversaries' goal.

As football developed in the 1860s and 1870s, the offside law proved the biggest argument between the clubs. Sheffield got rid of the "kick-throughs" by amending their laws so that one member of the defending side was required between a forward player and the opponents' goal. The Football Association also compromised slightly and adopted the Cambridge idea of three. Finally, Sheffield came into line with the F.A., and "three players" became the rule until 1925.

The change to the "two players" rule led to an immediate increase in goal-scoring. 4,700 goals were scored in 1,848 Football League games in 1924–25. This number rose to 6,373 goals (from the same number of games) in 1925–26.

Throughout the 1987–88 season, the GM Vauxhall Conference was used to test an experimental rule change, whereby no attacker could be offside directly from a free-kick. This change was not deemed a success, as the attacking team could pack the penalty area for any free-kick (or even have several players stand in front of the opposition goalkeeper) and the rule change was not introduced at a higher level.

In 1990 the law was amended to adjudge an attacker as onside if level with the second-to-last opponent. This change was part of a general movement by the game's authorities to make the rules more conducive to attacking football and help the game to flow more freely.[8]

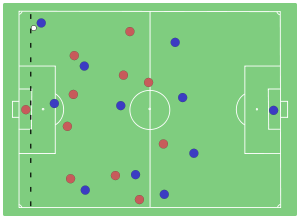

Offside trap

The offside trap is a defensive tactic designed to "trap" the attacking team into an offside position, pioneered in the early twentieth century by Notts County[9] and later adopted by influential Argentinian coach Osvaldo Zubeldía.[10] When an attacking player is making a run up the field with a team-mate ready to kick the ball up to him, all the defenders (except the goalkeeper) will move up-field in a relatively straight line in order to put the attacker behind them just before the ball is kicked, hence putting the attacker in an offside position at the moment when the ball is kicked.

The use of the trap can be a risky strategy as all defenders (except the goalkeeper) have to move up together in a relatively straight line, otherwise attacking players will not be in an offside position as long as the goalkeeper and one other defender are between them and the goal line. If the offside trap fails, the attacking players will have an almost clear run towards the goal. The 2003 rule changes have made it even more perilous as a tactic, since the definition of active play was made more stringent. Thus, teams attempting an offside trap are less likely to have an offside offence called when they have caught a player in an offside position, if he is deemed by the referee to be not in active play.

References

- ↑ Laws of the Game 2007/2008PDF (1.68 MB) (pages 35–36), FIFA, July 2007[update]

- ↑ Laws of the Game 2009/2010PDF (1.9 MB) (page 130), FIFA, February 2010[update]

- ↑ Laws of the Game 2009/2010PDF (1.9 MB) (page 102), FIFA, February 2010[update]

- ↑ Errors in judging 'offside' in football, doi:10.1038/35003639

- ↑ FB Maruenda (2009), An offside position in football cannot be detected in zero milliseconds, http://precedings.nature.com/documents/3835/version/1

- ↑ B Maruenda (2004), Can the human eye detect an offside position during a football match?, British Medical Journal, http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/329/7480/1470

- ↑ S Iwase, H Saito (2002), Tracking soccer player using multiple views, Proceedings of the IAPR Workshop on Machine Vision, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.143.9703&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- ↑ Offside history

- ↑ Guardian.co.uk, 13 April 2010, The Question: Why is the modern offside law a work of genius?

- ↑ FIFA.com

External links

- 2010/11 Laws of the Game - FIFA

- FIFA.com, FIFA Offside Presentation June 2005

- Offside explained at AskTheRef.com

- FIFA interactive guide